WRITING BY: BRIDGET HUBER // PHOTOGRAPHS BY: LAUREN OWENS LAMBERT // PUBLISHED JUNE 1, 2023 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

This story was produced in collaboration with the Food & Environment Reporting Network, a nonprofit investigative news organization.

A wave of startups say seaweed is a multi-pronged solution to climate change: It can absorb carbon, curb the effects of cattle's methane burps, and feed biofuels—not to mention the world.

The purples, golds, and greens of a variety of Gulf of Maine seaweed species shine through on a light table, including sugar kelp, sea lettuce, dulse, bladderwrack, and Irish moss. Seaweed is being heralded as a multifaceted solution to climate change, able to lock up carbon for hundreds of years, provide nutritious food for the world's population, contribute biomass to new types of fuels, and reduce greenhouse gases by providing cows a burp-free, methane-less diet. But many scientists warn against rushing into the kind of massive seaweed production required without first answering critical outstanding questions.

A bold experiment to use seaweed as part of a solution to climate change is underway in Iceland, where millions of basketball-size buoys made of wood and limestone and seeded with seaweed will be dropped into the ocean in the coming months.

The buoys—which look like bald mannikin heads with flowing seaweed locks below—are designed to sink to the deep ocean floor, where the carbon they contain will remain sequestered for 800 years or more, according to Running Tide, the Maine-based company behind the project. It's hard to pin down the timeframe: Nothing like this has ever been done before.

Running Tide is part of a new crop of startups that position seaweed as a multi-pronged solution to climate change—able to absorb atmospheric carbon, reduce cattle’s methane emissions, provide feedstock for biofuels, and feed the world—no fertilizers, fresh water, or even land required. Some of these ventures, like Running Tide, want to sink seaweed to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Others want to replace carbon-intensive materials like soy, fertilizers, plastic, and petroleum with seaweed-derived versions.

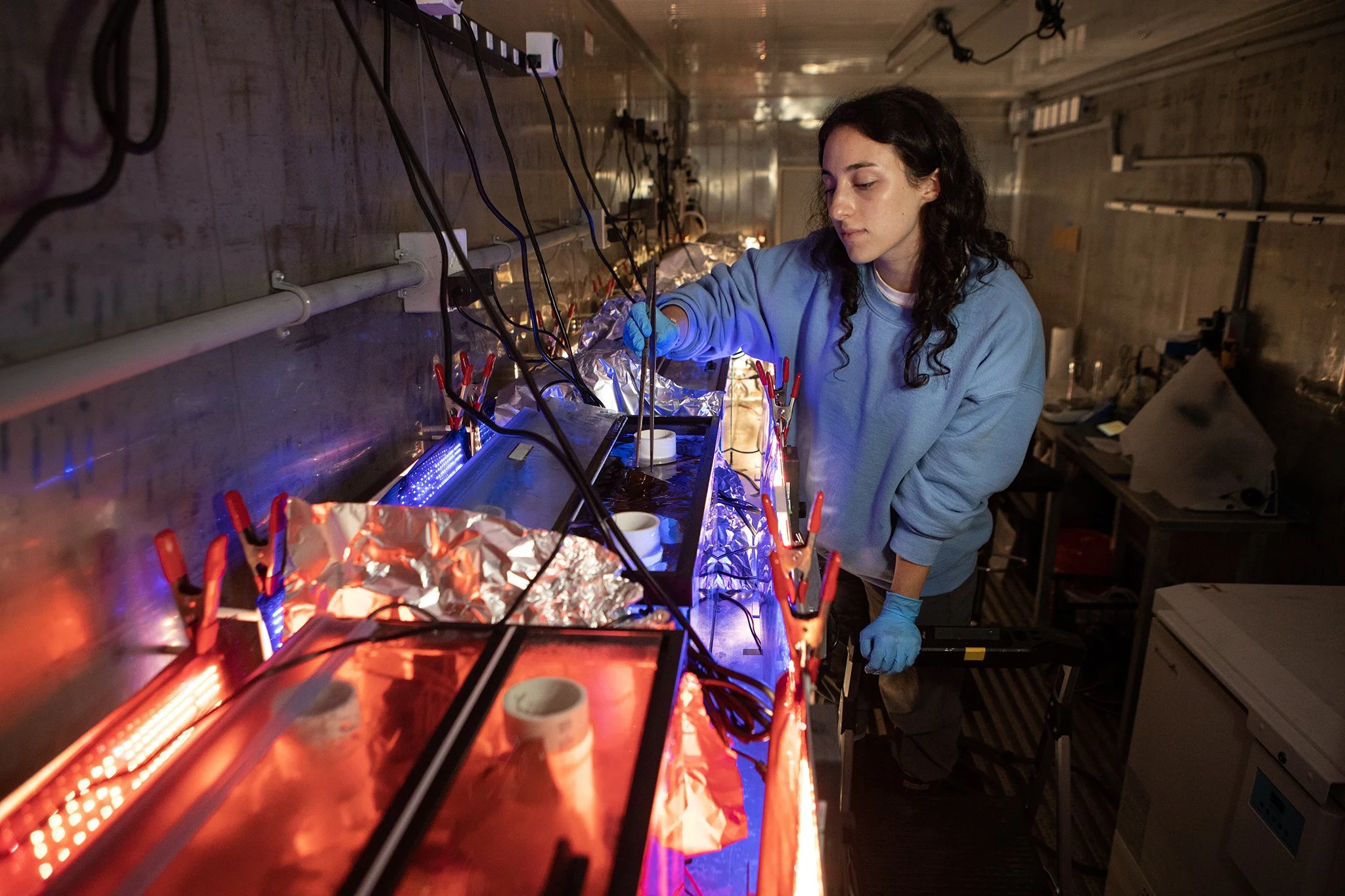

Natalie Colao, a technician at the Running Tide macro algae hatchery in Brunswick Maine, weighs and photographs individual kelp pieces weekly.

But if seaweed turned out to be an effective tool for stabilizing the climate, the industry would need to expand on a massive scale. Some scientists, small-scale harvesters, and environmental groups are cautioning against rushing ahead before fundamental scientific, environmental, regulatory, and ethical questions are answered.

Climate change is intensifying, and people are “panicking,” says Kristen Davis, professor of civil and environmental engineering and earth system science at University of California Irvine. But seizing on seaweed-based carbon removal as a solution before the science is settled, she says, could cause environmental harm or distract from more surefire strategies, such as swiftly cutting emissions.

“The science is not there yet to actually confirm that it’s a good idea,” Davis says.

Running Tide team members search for and collect kelp souris tissue and a variety of algae samples off of Jewell Island in Casco Bay, Maine. Souri are the reproductive tissue on kelp blades and are used to propagate kelp in the hatchery.

A potentially elegant solution

Running Tide, which operates on Portland’s fish pier, was founded by Marty Odlin, an engineer and fourth-generation commercial fisherman. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than nearly every other oceanic region, and Odlin has seen the changes firsthand: fish moving north to colder ocean, clam shells dissolving in acidifying waters.

About 15 years ago, Odlin heard a talk from Klaus Lackner—the physicist who popularized the idea of removing carbon from the atmosphere. It clicked. “It was like, Oh, this is right because there’s no way we’re going to get off fossil fuels in the next 50 years," he recalls thinking. "We’re going to have to pull it down.”

A recent assessment from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change echoes this idea. In addition to swiftly cutting emissions, the panel estimates that we’ll need to remove and sequester about 10 gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere per year by 2050, and double that by the end of the century. Right now, there are about 2,000 square kilometers’ worth of seaweed farms in the world; to sequester a tenth of a gigaton of carbon annually would require 73,000 square kilometers—equivalent to planting a nearly half-kilometer-wide belt of seaweed farms along the entire United States coastline, according to a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Using seaweed to draw down carbon would be an elegant solution—if it works. Seaweed forests collectively cover an estimated two million square kilometers and absorb as much carbon as the Amazon rainforest. But much of that sequestration is short lived. When the seaweed is harvested, eaten by animals, or washes ashore, its stored carbon is released back into the atmosphere.

Running Tide's model, in theory at least, would take that sequestered carbon and sink it to the ocean floor where, in the cold and dark conditions, it would remain for centuries, breaking down slowly. But tracking its fate will be difficult.

Top: Severine von Tscharner Welcome forages for seaweed at Reversing Falls in Cobscook Bay, Maine. Bottom Left: Bladerwrak seaweed found at Reversing Falls. Bottom Right: Von Tscharner Welcome dives for a seaweed sample.

Scientists aren't entirely sure how much carbon seaweed removes from the atmosphere, since that varies depending on location and weather. It's also hard to measure how much seaweed winds up on the deep ocean bottom as opposed to drifting elsewhere. And there are critical questions about how growing large amounts of seaweed or sinking it to the seafloor could affect marine ecosystems.

Cart before the horse?

In the last couple of years, Running Tide and other seaweed-based carbon dioxide removal ventures have gotten heat for racing ahead. The MIT Technology Review published a pair of critical articles. And scientists wrote in the journal Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture last year: “There is no need for another yet-to-be-proven technology-driven approach to climate change mitigation that is not based in sound science and marketability and distracts from other, more effective actions, like reducing reliance on fossil fuels.”

Red algae fills tanks at the Running Tide macro algae hatchery in Brunswick, Maine.

Another editorial, from some of the field’s most prominent scientists, argued that seaweed sinking ventures were "surging past even perfunctory evaluation of the environmental impacts and social benefits."

To build trust, Running Tide is working with an independent scientific advisory board and an auditing firm. It recently published a documentdetailing how it will account for how much carbon it is removing. Davis, who reviewed the paper, says it wasn't a bad start but that it was "a very general outline of a process that needs more detailed explanations to be actionable."

Technician Danny Chea checks algae for PH levels and temperature at the Running Tide macro algae hatchery.

Odlin says he takes the critiques seriously but sees no reason to wait until all issues are resolved. “We don’t have time to spend 15 to 30 years trying to answer questions that can only really be answered by actually going out and doing these things," he says.

"There’s a counterpoint to the precautionary principle and that’s the duty to intervene,” he says.

Time is of the essence

Amid a flurry of seaweed research , Davis was part of a team that recently modeled the costs and potential climate benefits of seaweed—the best emissions mitigation bang for buck. Sinking seaweed to sequester carbon, the researchers found, was much more expensive than using farmed seaweed to replace certain high-emissions foods, such as deforestation-linked soy.

Still, researchers cited a litany of potential challenges to seaweed as a climate solution no matter how it was used, including the high costs of seaweed-based carbon removal, potential ecosystem disruption, and the uncertainty that large markets for seaweed products exist. "The outlook for a massive scale-up of seaweed climate benefits is thus decidedly murky," they wrote.

“The amounts of seaweed that people are talking about are not realistic, at least in the extremely near future,” Davis says.

A Running Tide Kelp Field Operation team member on the hunt for kelp souris tissue. New kelp starts forming from the souris in September and October.